A podcast with unprecedented social impact

Desperate cries for help

As I prepare for my workweek as a court reporter, I comb through the hearing schedules of the 11 district courts and four courts of appeal in the Netherlands. Every week, I come across multiple criminal cases where a man is on trial for killing his wife.

A young man who stabbed his wife 200 times shortly after she gave birth, leaving their baby next to her body. A man who chained his wife to a heating pipe. A man who broke down his ex-partner’s apartment door in the middle of the night and shot her in the head. A man who strangled his wife and then tried to set her on fire.

These women all had one thing in common: they had ended or wanted to end their relationships. Most had suffered abuse, stalking or threats. And almost all had sought help from the police, social services or the justice system – without success. And then it was too late.

“We deliberately chose a podcast format because audio doesn’t just communicate facts – it conveys emotion and urgency”

There were so many cases that I had no choice but to dig deeper. My proposal found fertile ground with editor-in-chief from De Telegraaf Kamran Ullah. I formed a team with podcast producer Marieke Mager, co-host Wilson Boldewijn and experienced talk show editor Kelly Valk. We spoke with experts, police officers, a prosecutor, a forensic psychologist, a professor and lawyers.

But most importantly, we spoke with survivors of attacks by their ex-partners, with the loved ones of women who were no longer able to tell their own stories, and even with a perpetrator who had severely abused two consecutive partners. Fortunately, he hadn’t killed them – but, as he admitted, that wasn’t thanks to him.

Illusion of progressive society

These stories deserved more than just statistics and case files. We deliberately chose a podcast format because audio doesn’t just communicate facts – it conveys emotion and urgency. The voices of survivors, loved ones and experts add layers of depth that written text alone cannot always capture.

“The eight-episode podcast hit like a bombshell. Suddenly, the term ‘femicide’ was being used in courtrooms”

Our investigation made me realise that the belief we live in a progressive, gender-equal country is an illusion. Yes, on paper, men and women have equal opportunities. In reality, women still earn less than men for the same work. Women’s health issues are often overlooked because male symptoms are considered the standard. And women who try to report abuse, threats or stalking to police are routinely dismissed with: “Well, ma’am, if he hasn’t done anything, there’s nothing we can do.”

Not done anything? Abuse, threats and stalking are all criminal offences. There is a deep undercurrent of sexism in our society that results in women not being taken seriously. That is shocking – because it costs a woman her life every eight to 10 days. In fact, femicide claims more victims than organised crime.

Giving a voice to an unseen issue

Each strangled, stabbed, shot or beaten woman is treated as an isolated incident. In reality, they are symptoms of a larger pattern of gender inequality in our society.

Even high-profile cases – like that of 16-year-old Hümeyra, who was shot dead by her ex-boyfriend in front of her classmates at her school in Rotterdam – fail to bring real change. That day, she had been due to file her fifth police report against him. I watched as people expressed shock and outrage, as yet another investigation was launched, which – predictably – revealed what had gone wrong. And I watched as that report was placed on top of a pile of previous reports in a desk drawer. Without anything changing.

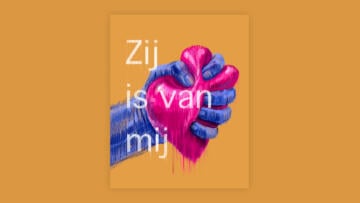

That is precisely what we exposed in Zij is van mij (She Belongs to Me). The eight-episode podcast hit like a bombshell. Suddenly, the term “femicide” was being used in courtrooms. My inbox was flooded with messages from women fearing for their lives, desperately seeking help.

I am not a social worker. I can’t make a difference in that way. But with this podcast, we gave a voice to something that needed to be said. And the microphone proved to be a powerful weapon. Requests for interviews and invitations poured in – from police departments, public prosecutors’ offices, support organisations, mayors and politicians who wanted to hear about our findings.

At first, I thought: This is absurd. You should be telling me how things work, not the other way around. But I seized the opportunity. Whenever I can, I make time in my workweek to give lectures about femicide. The more attention, the better. Winning a Dutch Podcast Award for Zij is van mij helped amplify the message. But we are far from done.